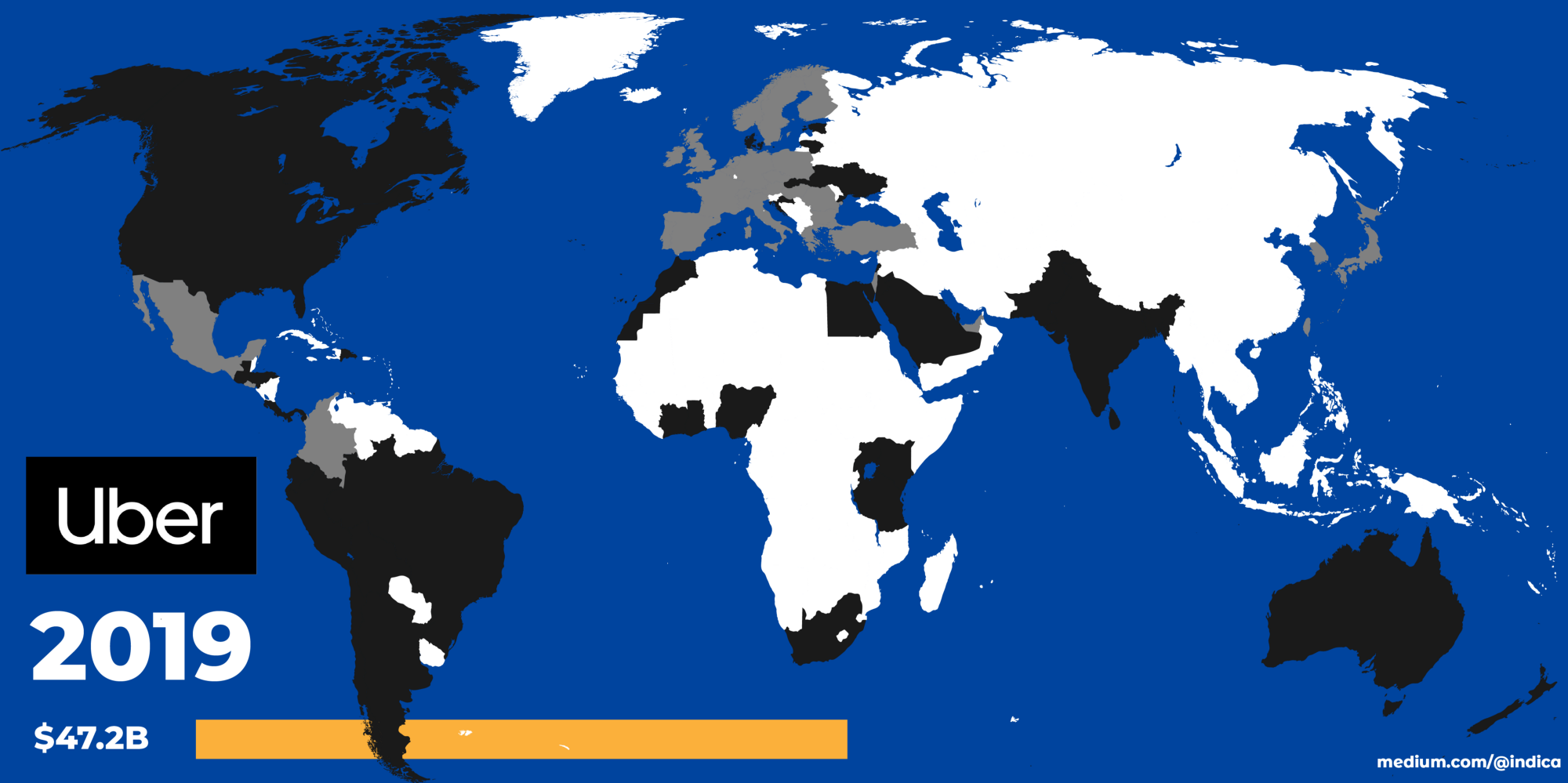

Uber’s Rise And Fall In One Map

How Uber won and lost the world

You can watch the rise and fall of Uber in this GIF. From 2010, Uber black spreads across the globe. Then in 2014 Europe starts to go grey as regulation kicks in. Then Asia goes white as the company goes into full retreat. The investors manage to get their money out in time, and the public markets are stuck with this rapidly declining turd. It’s a hell of a ride.

2010 — UberCab

UberCab was dreamt of in 2008, launched in 2009 and carried its first passenger (in San Francisco) in 2010. It was and is magic. Push a button and get a ride.

Uber hit that startup sweet spot — a product that both masses and Venture Capitalists could actually use. America was also an ideal market— a country with widening inequality, where people wanted to have servants but didn’t want to call it that.

Uber lets people have drivers and be drivers without looking at either the economic or social problems too closely. Just push a button, get a ride.

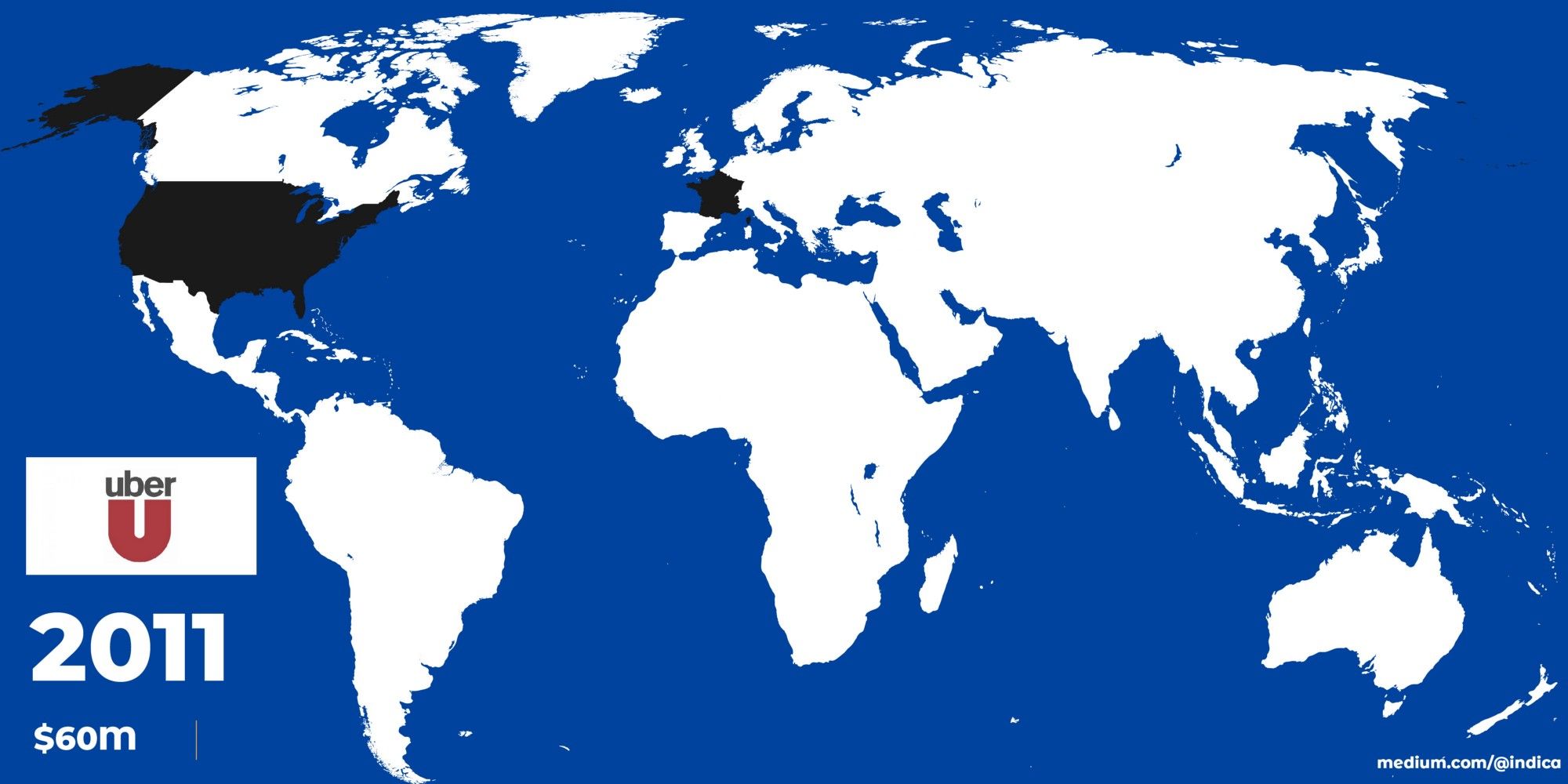

2011 — Uber

In 2011, UberCab changed its name to Uber, to avoid regulation. This was more than a name change, it was (and is) core to Uber’s being. Uber’s two core innovations were actually not technical. The first was to break economic laws, and the other was to break labor laws. The secret sauce was how they got away with it for so long.

Economic Laws

I took some remedial business school and the first thing they taught us was about fixed and variable costs. A gun is a fixed cost. Bullets are variable.

No firm will sell below their variable cost, in this case, the cost of a ride. Otherwise, you’re just selling a dollar for 50 cents. I was taught this as essentially a law. Uber broke that law — subsidizing both the rider and the driver — and saw explosive growth. They continually lost money on a unit basis, pricing any rational firm out of the market and continuing expand. Their losses also expanded, but no one seemed to care.

Labor Laws

The other law they broke was much more real, but they got away with it anyways. People fought for labor laws for decades and jobs now come with certain rights, which are expenses to an employer. Uber was just like, ‘what if we just don’t call them jobs?’ and the world was like, ‘yeah, OK’. For a while.

Uber likes to call drivers independent contractors, but I’ve worked inside a ride-hailing company and the business runs on people that drive every day. They want (and get) the benefits of full-time employees without the costs. Which is obviously a competitive advantage.

If you price below variable cost and don’t pay the same labor costs, of course, you’ll compete with more economic firms out of the market. Of course, you’ll grow. And Uber did.

Uber got away with it because of the name change, and the ‘tech’ halo that was still keeping regulation at bay. 2011 was also the year that Uber expanded to France. Europe would prove to be its regulatory Waterloo, but not yet.

2012 — Uber White

In 2012 Uber spread across the ‘western’ world, ie wherever white, English speaking people live. The US, Canada, UK, Australia and France (which gave English most its big words).

Growth was explosive. The product worked like magic and was becoming magically cheap as it became more and more divorced from traditional economics. The company’s valuation squared from $60 million to $346.5. This was just the beginning.

A massive amount of ‘cheap’ capital (at a time when poor people struggled to survive) was about to subsidize middle-class lifestyles and make a few people billionaires.

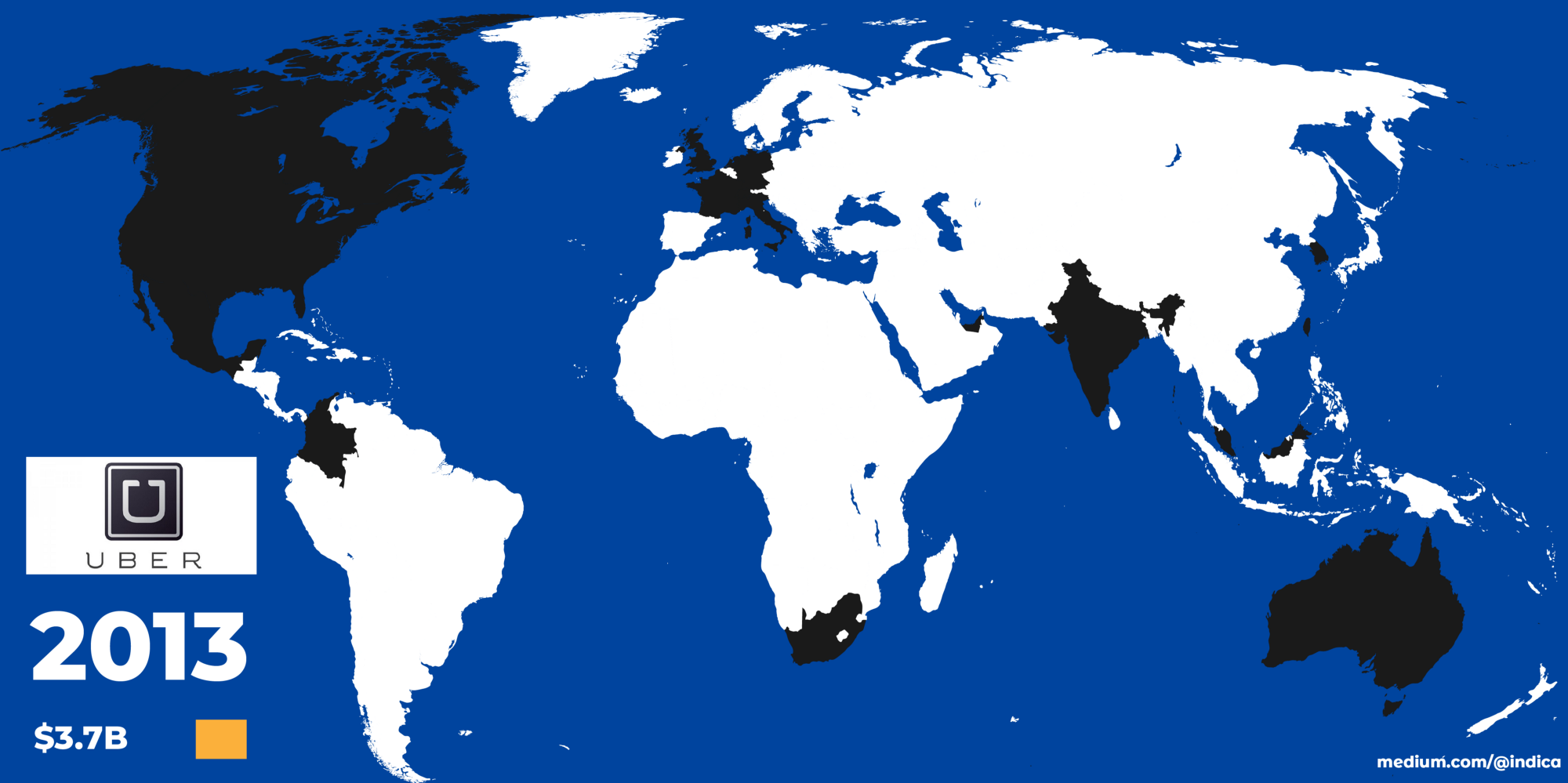

2013 — Three Comma Club

In 2013, Uber went brown, to a truly mass market in India. They also launched in South Africa, Germany, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Mexico, and the UAE. Ride-hailing went from millions of potential users to billions, and their valuation increased accordingly. Uber joined the three comma club.

Their investors went from individuals like Jay-Z and Jeff Bezos to all institutions. Uber’s Series C from Google Ventures (GV) valued them at $3.7 billion, and that was just the beginning.

I’ve competed against Uber, and whatever you say about them, the company can execute. They put numbers on the board. Numbers disconnected from any economic reality, but that takes a while to kick in. We’re not there yet.

These are the good days. Cocaine is on the table and the lights are low.

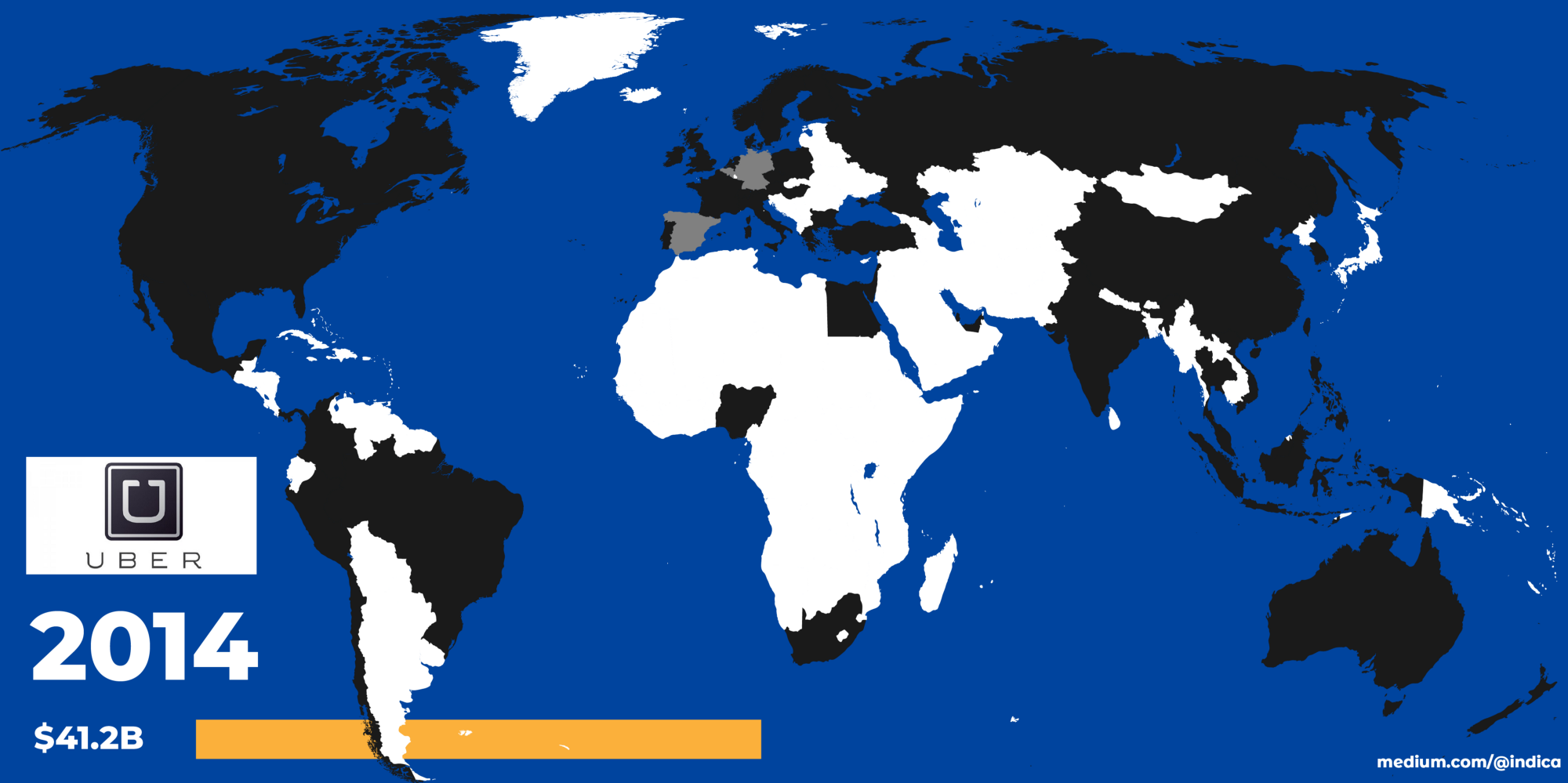

2014 — World Domination

2014 was the year of world domination. Uber had spread to every inhabited continent on the globe. With China, Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, and Egypt, Uber offered investors exposure to almost all growth across the globe.

At this point, however, the herd immunity of democracies was slowly kicking in, and the competition was biting back. Europe began banning Uber, first in France and then Berlin. It took a while for these bans and regulations to work through the courts, but it never got better.

At the same time, companies like Didi and Lyft and Grab showed that cheap capital was no longer an advantage, and smaller, more nimble companies took lesser markets from Uber, like PickMe where I worked, in Sri Lanka.

In a Napoleonic or blitzkrieg attack, you depend on a small force to shatter enemy lines and hopefully get them to scatter or give up. Time, however, is not on your side. If the enemy has time to regroup, they are bigger than you and will eventually win.

Uber had rapidly smashed through regulation and competition, but time was not on their side. These two forces eventually formed a pincer movement that would choke and ultimately drive the company back. But not yet. This was still the Travis era. The triumph of the will.

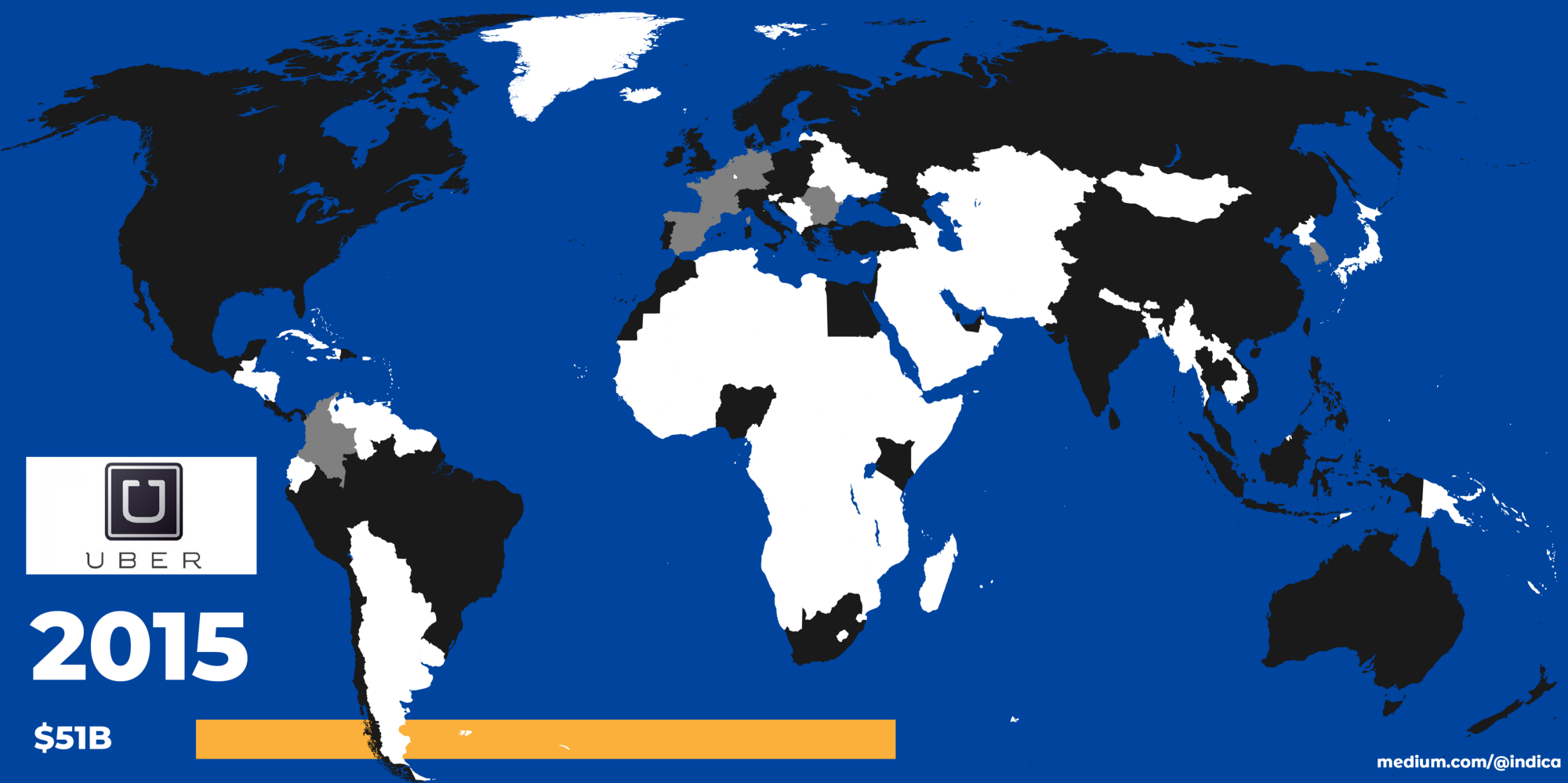

2015 —The High Water Mark

No one knew this at the time, but 2015 was the best it would ever be for Uber. Uber expanded into my country, Sri Lanka, and its valuation ($51B) was rapidly approaching our GDP ($80B). If you look at the map above, this is the furthest Uber would spread, and it was already beginning to roll back.

This year saw small additions — Sri Lanka, Morocco, Costa Rica, Lithuania — and big setbacks. The regulation cancer in Europe had spread to Spain and gone around the Maginot Line to Belgium and the Netherlands, and then east to Romania. Uber would continue to operate in Europe, but at a diminished and highly-regulated level (for them). This cancer had also spread to Korea.

Travis Kalanick had reached the limits of blitzkrieg warfare, though he didn’t know it. No leader seems to, but it happens. Eventually, your troops get tired, the methamphetamine wears off and the board takes you into the bunker for a chat.

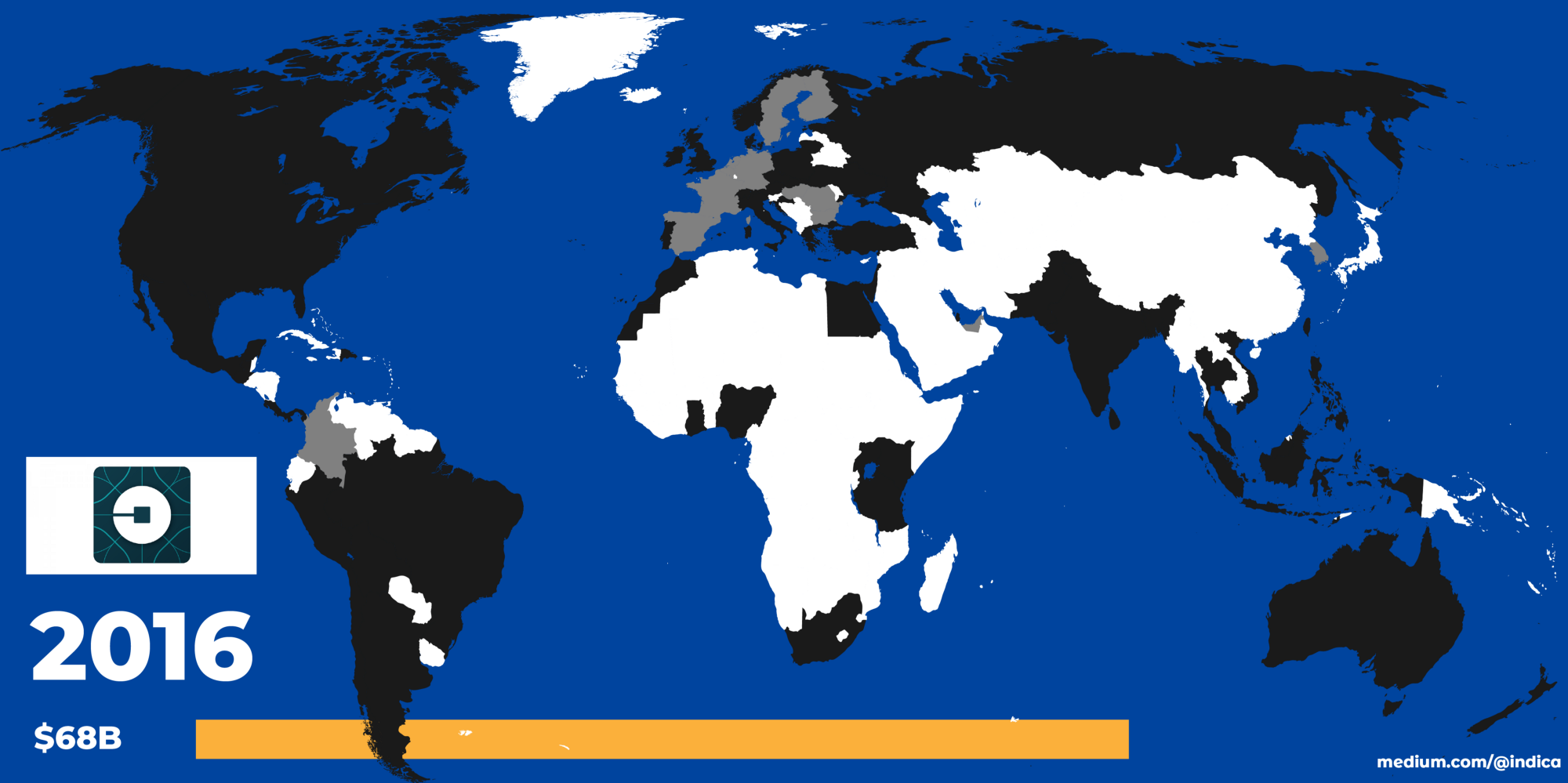

2016 — New logo. Does not save company

In 2016, Uber changed its logo to some sort of digital sperm. This did not help. Uber withdrew from China after heavy losses, the first blood in the water, and not the last. As a parting gift, they got 15% of Didi, but Uber would never be a truly global company now. They were being pushed back west, and also losing Europe.

The regulation had spread to Scandanavia now, and eventually the UK. These regulations were a threat to Uber’s core business model, which was signing up anyone with a car. Uber was forcing Uber to work with licensed drivers and companies, to essentially become UberCab again. The tech halo was coming off, and Uber was getting a more devilish reputation in the press.

Uber’s valuation was still going up, to $68B, but they’re scraping the bottom of the barrel now. This time it’s blood money, from Saudi Arabia. Saudi is one of the most objectively evil autocracies in the world, a petrostate built on climate change and human rights violations. Uber now had murderers on their board. This would come up later.

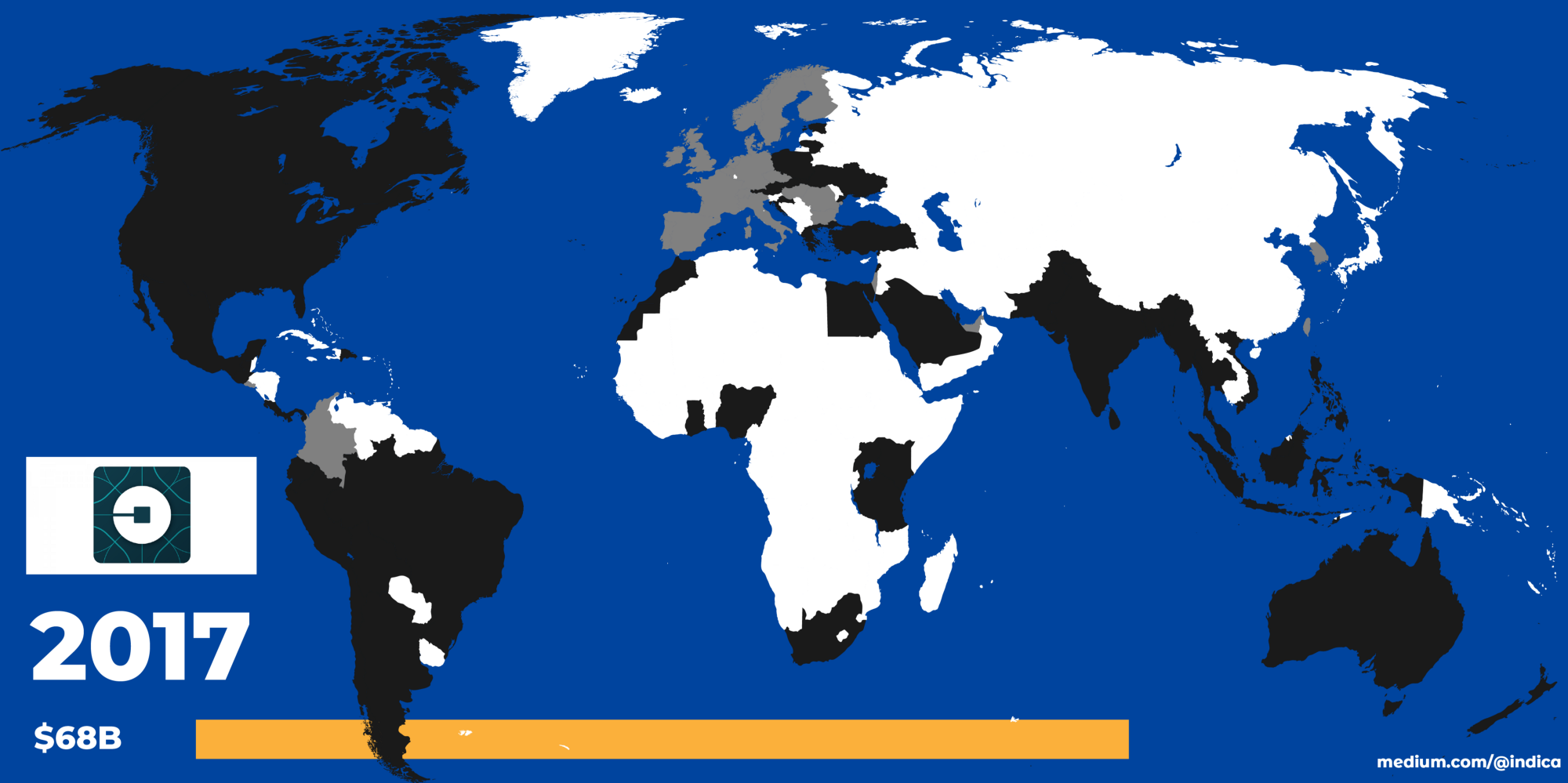

2017 — New leader. Sorta saves company

By mid-2017 Travis Kalinick was out and the much more responsible Dara Khosrowshahi was in. He had one job. Get this turd over the IPO finish line so that early investors could get their money out. There were still enough animal spirits in the market to ignore the obvious, but he didn’t have much time.

At this point, Europe is essentially lost and the UK has fallen (for the first time). Uber exists there but it’s on its way to being regulated into a commodity. Russia is also lost. Uber exits with a minority (now 35%) stake in Yandex’s hailing business, but it’s still an exit.

Note that I’ve whited-out these exits on the map, but they’re not of zero value. Uber will never be a truly global cab company, but in retreat, it has become a holding company for global assets. Like Yahoo’s stake in Alibaba, this isn’t nothing, and could potentially be worth a lot.

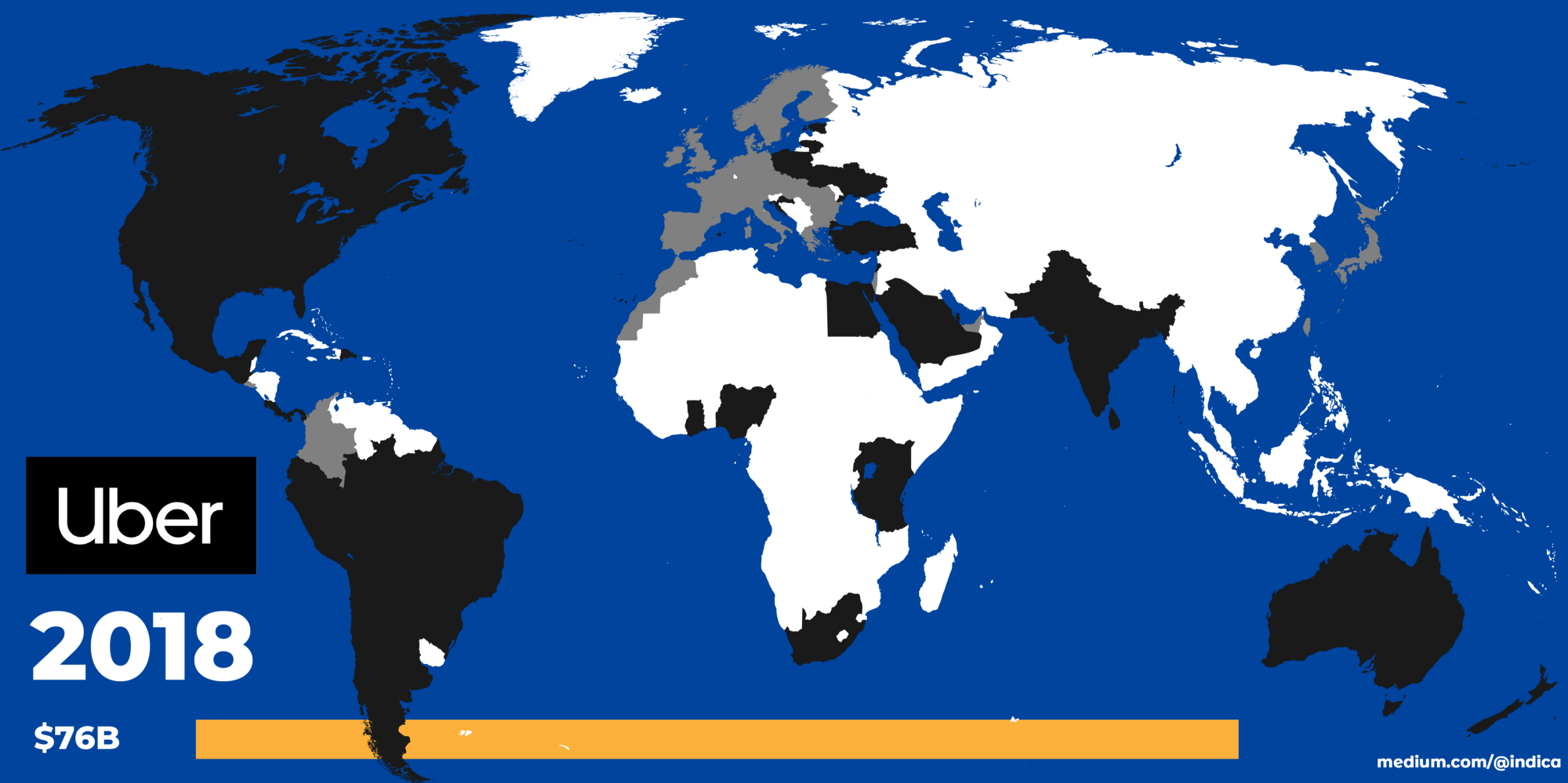

2018 — Loss Of Southeast Asia

At this point, the shitty business model of regulated cabs is becoming a default. Uber launches in Japan, but as the frontend for a cab company. Cabs is a shitty business already and food delivery (UberEats) is a shitty business in the future, but Dara just has to keep rolling this turd over the finish line. And he’s almost there.

Before that, however, he has to take one major hit in Southeast Asia, namely all of it. Uber exits the market for what becomes a 23% stake in Grab. Only India (and Sri Lanka) remain in Asia, but I also think this is a matter of time. Uber started a ground war in Asia and lost, like everybody else in history.

Europe is totally gone and this regulation contagion is spreading to Morocco and who knows where. In its last private round Uber is valued at $76 billion, but for a relatively paltry investment of $500 million from Toyota. As you can see these private valuations are meaningless and set a misleading peg for the IPO, which is exactly what Uber wants to do. The pyramid scheme is almost complete and it’s time to unload this turd on retail investors. Yay pensions funds.

Come on Dara, you old dung beetle, you’re almost there!

2019 — Cashing out before crashing out

The pharaohs respected dung beetles and Uber’s investors better respect Dara. He did it. By just being a responsible manager he manages to cover up a crumbling business model and the company successfully IPOs in May of 2019. By successfully I don’t mean being a good investment, I just mean enabling the pharoahs to cash out while everyone else gets buried alive.

The stock lists at an $82.4 billion market cap, far down from estimates of $120 billion, but who cares. Early investors get paid, the Saudis get paid, Travis gets paid. In Q3 Uber shells out $3.9 billion in stock-compensation so by November even employees get paid. At this point, the stock has dropped nearly 40% but the pyramid scheme is complete and retail investors are holding the bag.

Luckily it’s not a complete sham and there’s something there, just not an 80 billion-dollar company. If you look at the maps, retailers paid 2020 prices for a company rapidly receding back to 2013.

And the retreat continues. Uber will likely exit India (at least UberEats), regulation is coming to its core market of America and they just got kicked out of London, again. Uber is smart and they execute like the guillotine, so maybe they’ll surprise me, but it’s hard to escape a global pincer movement.

Competition and regulation are slow, stupid forces, but they do catch up with everyone in the end. You can’t win a land war in Asia. You can’t sell below your variable cost. You have to follow labor laws.

Uber’s core innovation has been outrunning reality for a decade now. They’ve emitted a bunch of carbon, increased traffic, worn-out poor peoples’ cars and told everyone it was a tech company. And we loved it. It’s been a lot of things, but this I know for sure. It’s been one hell of a ride.

Sources, Data, And Assumptions

I’ve attached my sources, data, and assumptions below. I made this in my brain so it may have errors, please correct.

Uber’s Logo Changes

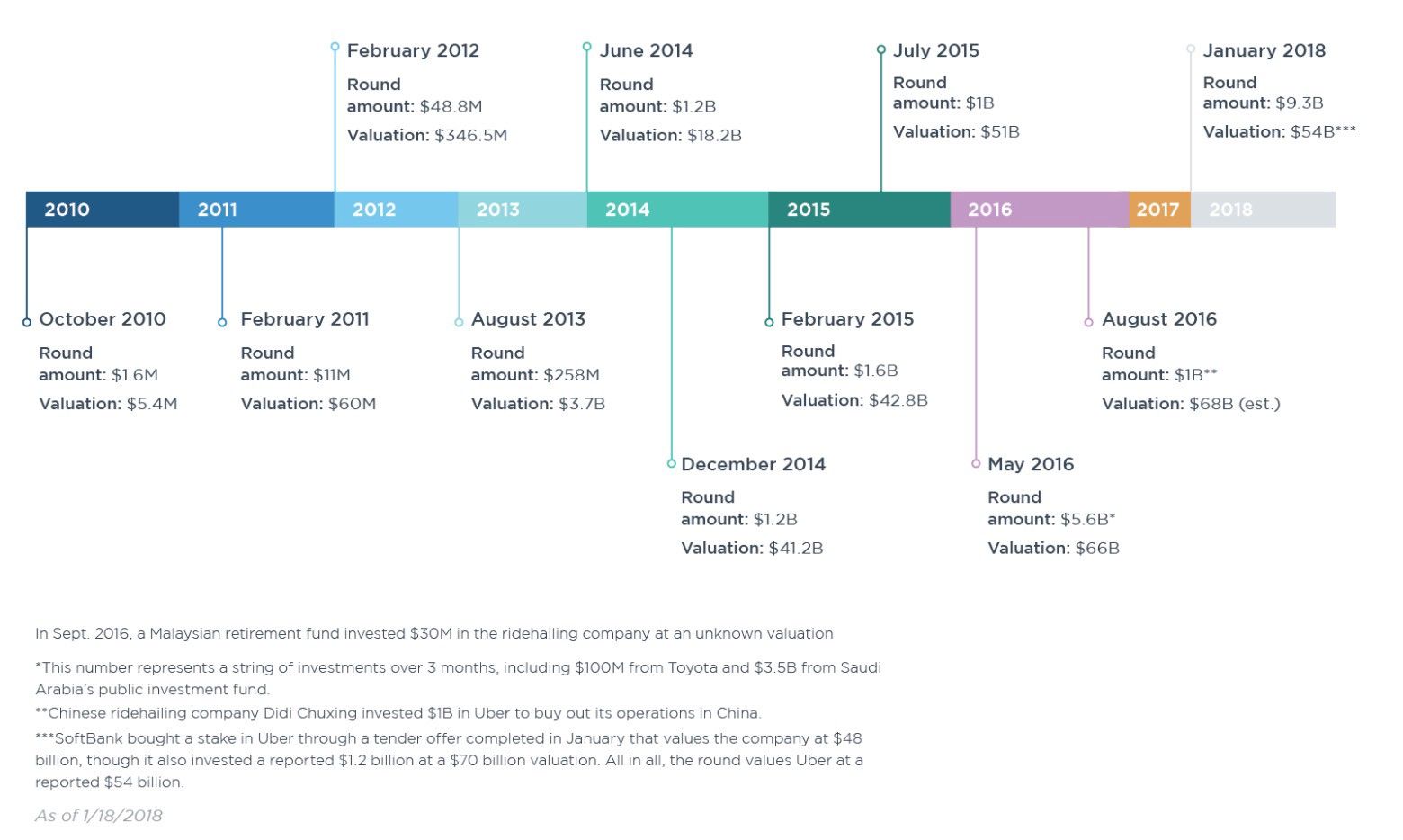

Uber’s Valuation

For the valuation numbers, I went by Pitchbook up till 1/2018 and craft.co for further information. Note that Uber would sometimes have multiple rounds in a year. I displayed the number at the end of the (calendar) year.

Uber’s Global Expansion

Finding the dates of each Uber launch is actually really difficult. There isn’t one resource so I had to dig through Uber blogs, Twitter accounts and a lot of news articles. I’m sure I’ve missed some, so please let me know.

Note that I haven’t included the implications of Uber’s acquisition of Careem (which would add hundreds of cities in the Middle East and Africa) because that deal is still going through.

2010

2011

2012

Netherlands

United Kingdom

Australia

Canada

2013

Germany

Korea

UAE

Italy

Switzerland

Taiwan

Singapore

Malaysia

Mexico

India

South Africa

2014

Belgium

Spain

Bulgaria

Finland

Hungary

China

Sweden

Denmark

Russia

Israel

Norway

Portugal

Indonesia

Vietnam

Thailand

Philippines

Greece

Austria

Poland

Turkey

Brazil

Peru

Chile

Bahrain

Czech Republic

Egypt

Hong Kong

Ireland

Lebanon

New Zealand

Nigeria

Panama

Qatar

2015

Romania

Macao

Morocco

Slovakia

Sri Lanka

Costa Rica

Croatia

Dominican Republic

Estonia

Kenya

Lithuania

2016

Argentina

Bangladesh

Bolivia

Ghana

Guatemala

Pakistan

Tanzania

Uganda

Ukraine

2017

Myanmar

Ecuador

El Salvador

Saudi Arabia

2018

2019

Ivory Coast

Honduras

Jordan

Uber’s Global Retreat

There is a Wikipedia page for ridesharing legal issues, but I still had to check original sources for each item and again, probably missed some. Note that I have noted Uber as in retreat on the country level if the legal action happens in a city, with the exception of the USA.

In most cases, retreat means being ruled illegal, or having law passed regulating Uber. In rare cases, they are banned outright, and even rarer is for the order to be immediately enforced. Then there are the complete exits due to competition.

2014

2015

France

Netherlands

Korea

Bulgaria

Romania

Columbia

2016

2017

United Kingdom

Italy

Switzerland

Taiwan

Denmark

Russia

Israel

Norway

Portugal

Macao

Czech Republic

Ireland

El Salvador

2018

Singapore

Indonesia

Vietnam

Thailand

Malaysia

Philippines

Myanmar

Cambodia

Greece

Austria

Morocco

Slovakia