The Border Down The Middle Of My Pants

Life with two passports

I was born on a border, but I didn’t know it. I didn’t know anything. I was a baby. I wish I had some memories or stories to tell you, to make my story more real to you, but I remember nothing. It’s barely real to me, just a set of photographs, some stories, and paperwork. I was born in Canada and so I am Canadian. I had nothing to do with this at all.

I am also Sri Lankan, but this has even less to do with me. I am Sri Lankan through my father, and only my father, because the law at the time only allowed men to pass citizenship. I am Sri Lankan by descent, something I cannot possibly remember or effect because it, by definition, has nothing to do with me.

In that sense, I’m an apple that fell far from the tree. Still an apple and also, apparently, an orange.

So I just am. I am Canadian and I am Sri Lanka. This combination is well nigh pointless except for one thing. I can see borders. Because one runs through me. Most people cannot. More than mountains, more than rivers, more even than oceans, these are the hardest divisions in the world today. You can stretch a piece of paper across them, but without that they are more hostile than the roughest sea.

Instant Noodles

My friend used to sell noodles. Instant noodles. He said that their sales would go up in certain coastal towns as Sri Lankans prepared to push off to sea. Even us, fellow brown people, would laugh at them. Boat people. Australians call them illegal and encourage them to drown at sea, or throw them in concentration camps.

I call them incredibly brave. They’re heroes. I couldn’t do it. They throw their bodies against an unjust system, end up deported, in concentration camps, or dead. And yet they form the numbers, the sacrifice that forms a growing monument to shame. They die to show the absurdity of borders. They’re willing to die to live.

But I’m not brave like that. I am not a body tossed against a border, I am an idle mind in an airport. I expect my meals on time and my flights to connect. I am a person with rights and expect to be treated as such. I am not brave. If anything, I am complicit. My only value is that I am not blind.

Privilege is hard to see if you’re born into it. It’s like asking a fish how the water is. What’s water? It’s a bit easier if you’re amphibious, if you’re comfortable on both water and land. I am a frog in that sense. I know what’s water because I’ve been outside.

Pockets

I think about it every time I’m in an immigration queue. Because there’s time to think. I pat my pockets and am always reassured to find my passport. Because that’s me. And I wonder, ‘that’s me?’ This one document, held by pockets of cloth, am I reduced to this? If it slips out in the toilet, where do I go? Do I disappear? Am I stuck in this airport forever?

It’s an idle thought. Like taking a peak off a cliff. You hold the railing, grin at your companions and go get something to eat. But the cliff is real. There are bodies down there.

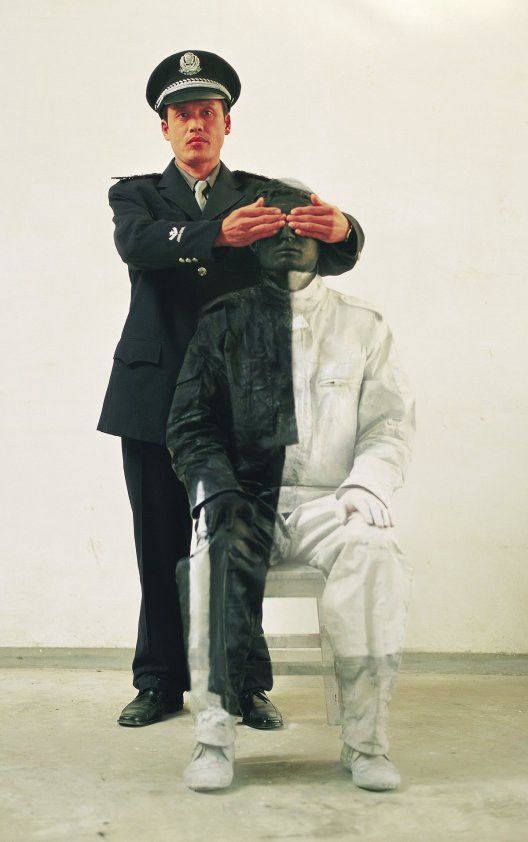

Every time I travel I am being arrested. So are you. Those border guards are cops and there are cells just out of sight. We let this go because they let us go, but we never stop to question if this is right. I’d argue that it isn’t. They have no right to arrest us for moving across the earth. Just because they let you go doesn’t make it right.

But I didn’t question this until recently. I’d just feel my Sri Lankan passport on one side and laugh. I don’t even need it to get into Sri Lanka. It actively gets me out of most places. It’s like looking for money and finding a note that says ‘go fuck yourself’. It’s funny. I mean, it’s funny because I have another side. I have a Canadian passport that gets me waved through almost any line. I’m literally in a position to laugh. With one step of my other leg, I’m on the other side.

I think about this often, this border running down the middle of my pants. It’s like my Canadian side can walk the earth and the Sri Lankan side is lame. The border divides my nuts as well, right now one child is British (his mum) and the other Sri Lankan. It’s a bureaucratic quirk, until we do some paperwork. The child is fine, we’re just tourists in border purgatory. But some people live here. And their kids are no less deserving of the world than mine. There but for the grace of pockets go I.

As I stand in the airport, I think ‘this is absurd’. I am human. I am not my birthplace, I am not my parents, I am not a document. I’m a human and I deserve to be free. I understand being arrested for what I do, but why am I being arrested for what I am?

But then I walk through that line and I am free, and I forget that I was briefly under arrest. And this is just the way it is, so I forget about everybody else in line. I just want them to move faster. I just wish I’d chosen the other line. I rarely stop to think why is there a line at all. But I’m thinking about it now.

This is that question. Why are we ruled by our pants, or our purses, or what we carry in our hands? It’s an obvious question buried under chains so casual they are invisible. But it’s a question we must ask. Why aren’t we free? Who has any right to ask what’s in my pockets? Why do I need a permission slip from a sovereign or state? I have a good passport and a bad passport and I must ask, why do we need passports at all? What’s wrong with being free?