No Brain Is An Island

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main… John Donne

No brain is an island, entwined only with itself; every human is a piece of the network, a part of the mainframe. We have networks of cognition and emotion that spread well outside of our body; we think with our loved ones, and when they are ripped away we feel a physical pain. Self-help is impossible when we are actually not-self, when we’re not just individuals but different illusions sustained on many different planes.

What I express the modern metaphors of neuroscience and computers has long been known. It’s just that in this godless age we can only understand ourselves as machines. But the old understanding is still there, lumped under superstition and filed away. Where I live, in Sri Lanka, one of the traditional ‘mental health’ interventions is a ‘demon’ dance, performed with and for the whole community. I was struck by this similarity when I read a history of the Maya, describing the same concept:

“instead of seeing illness as an isolated, purely physical phenomenon, the shaman treats it within the context of the tensions and anxieties of interfamilial and social relationships. The curing of an individual is more than a healing of the physical being, It is a healing of the emotional being, the social being, and the social web holding the community together.” (A Forest Of Kings, Schele and Friedel)

I think about this because I’m thinking about Dooce (Heather B. Armstrong, one of the first bloggers I followed). Because she’s gone now. I read her sadly prescient book The Valedictorian Of Being Dead. She describes undergoing therapy to put her under with propofol (the Michael Jackson drug) in the hopes of turning her brain off and putting it on again. She brought her Mormon mother and eventually her whole family. Dooce was literally comatose for the whole process, and her mother described it to her.

“Well, Dr. Tadler held up the propofol and said he was ready to start. Do you remember that?”

Oddly, I hadn’t remembered that part, and I usually did. I only remember looking up and seeing September’s [her sister] face, her concern and her worry.

“She saw your arms fall to your sides as you went under and she did not say a single word the whole time you were out.”

“The whole time?” That’s a long time to remain silent. I know it varied, the time it took me to wake up out of the anesthesia, but it was never less than seventy-five to ninety minutes from beginning to end.

“The whole time,” my mother repeated. “In fact — and she told me I could tell you this — she cried the entire time. She cried, silently. Tears just rolled out of her eyes and didn’t stop until you took that first breath on your own.”

“I . . . I don’t know what to say.”

“I knew what she was feeling, and I told her that we were witnessing something sacred, something very spiritual.”

“That if I attended any church, this would be it?”

My mom didn’t laugh but gave me a gentle look. “No, it’s so much more than that. Those people in that room have your life in their hands, and they don’t have a machine telling them how much propofol to give you, or how far to take you down, or how long to keep you there. They are all working together as a team and trusting each other with the trust you have put in them.”

…

“What you are going through is so sacred, Heather,” my mom repeated. “To be in that room with you, to witness your bravery . . .”

I think of her mother, her siblings, her children; I think of her as someone who knew her only through the networks of the internet and how it rings my emotions. I think of the violent death in my own family and my heart reverberates. As John Donne said, “any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

In her book Dooce was literally under for the treatment, the book is really about her family, her relationships, her connections. All the things which make life worth living, which is a clue. It’s not that these are isolated things which make life worth living for an isolated individual. The things that make life worth living are life itself. We are our connections. No human is an island, as much as we drown in oceans of tears.

In this way medicine is bumping hard into the philosophical limits of science. The most robust effect they’ve ever found is ‘placebo’, and the isolated, generic individual they try to treat is actually, in itself, a deeply pathological and often fatal state.

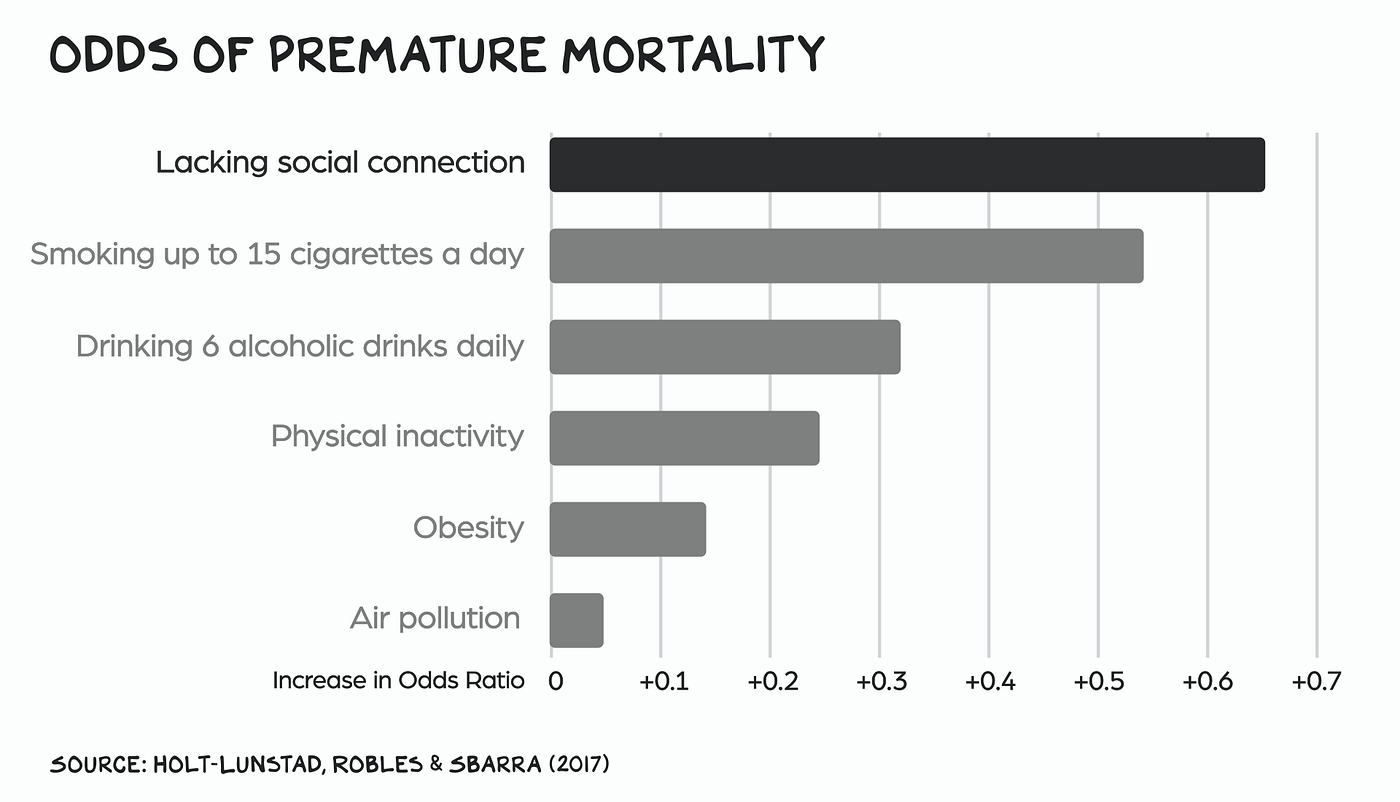

Modern society has killed god and driven a highway through the family and can only understand the obvious through ‘studies’. Being isolated makes human beings miserable, it’s worse than smoking cigarettes and drinking every day. Indeed it’s a good reason to numb yourself with drugs as a tortured lab rat does. It’s not true that lab rats will just push a lever for drugs all the time if it’s available. If they’re given family and social connections and a life they don’t do it. It’s only when they’re torn away from their connections to be studied that they behave in this self-medicating way. Have we considered that the people reading the studies might be in the same sort of cage?

Dooce’s therapy involved completely passing out from a combination of propofol and other drugs, including fentanyl until that made her hallucinate. This struck me because it’s what so many people in Mess-Of-America do to self-medicate. The opioid crisis there is people taking brain-deadening amounts of heroin, oxy, fentanyl or whatever they can get their hands on, only outside of a hospital and outside of care like Dooce had. Instead people take drugs on street-corners or basements or motel, often ending up in jail. For people with good insurance the sacred, for those without, the profane. And these poor, suffering people get targeted in a ‘War On Drugs’, ignoring the warlike, atomized society that makes them feel this way.

I say this is medicine bumping into the philosophical limits of science because the latter day ‘enlightenment’ (I mean, Buddha did it much earlier) placed a primacy on the individual and their capacity to know everything. Now God is dead, rituals go unobserved, and the supposedly infinite understanding of science has to be filtered through two priesthoods of scientists and then journalists, to tell us obvious things like being lonely sucks. We — meaning the West that everyone else is supposed to ‘develop’ into — have lost our way. Deeply lost our way. Not on a medical or scientific level, but at the level of philosophy, and the spirituality with which the concept of philosophy used to be inseparable from. Now we have separated philosophy from religion, knowledge from wisdom, and we find ourselves separated from our selves and shuddering in pain.

I’m not criticizing Dooce’s doctors or her treatment at all. God bless them, she got at least 18 months of good living out of it and I’m not the judge of what anyone does to feel better. I am just asking, how did it get this bad? Can we get our by banging harder on the ‘individual’ assumption inherent to psychology, or did we lose some vital wisdom along the way? Again I return to the fact that the placebo effect is the most robust in psychology. Hence in the epilogue on Dooce’s treatment, her doctor said other explanations could account for her recovery as well. As she wrote:

“Those other explanations, he told me, included things like the natural history of the disease — many depressive episodes will end on their own because they are situational. There’s also the placebo effect to consider, as well as all the attention a patient is suddenly receiving from medical staff and family members.”

Modern doctors and scientists are constantly trying to isolate variables. I studied psychology and it’s build on a foundation of tortured animals, separated from their families and ruthlessly experimented on. On top of that, human studies are almost always based on isolated individuals, either isolated in labs or demographically sorted and analyzed that way. Everything else, every other possible effect, is lumped under placebo and traditional interventions are called superstition and completely ignored. Science is all about finding isolated answers, but what if isolation is the problem?

We think it obvious that because we have a brain and we can turn it into numbers that it must work that way, but this has never been the ancient understanding of existence, and in your own existence, surely you know better. The greatest proof that we are more than the sum or our internal organs is that we can feel pain in other peoples bodies.

I feel Dooce’s pain from thousands of miles away, just as I feel the pain on my beloved Din Anna’s five-month death anniversary today. In our family we have been mourning my grandfathers death for over 50 years, in a dhane gathering where we feed monks and they pass a sacred thread around that we all hold together. Is it ‘real’, is it scientific, or is it just superstition? Believing in a sacred thread is considered foolish by many, but to me the greater folly is missing the higher wisdom in the ritual, the meaning of the symbol. Of course we are connected, and that white thread is just the way of saying it. No brain is an island. We’re all a part of something higher. Maybe being disconnected from that is why we feel so low these days.