A Normal Person From 20 Years Ago Would Look Like A Monk Today

When I took out a smartphone at a baseball game in 2002, I was the only one in the whole stadium. I looked weird as hell to my friends, chatting to someone in the UK over GPRS. Now everyone has a smartphone. Any stadium can instantly turn into a festival of flashes. We forget how weird this is. It’s weird.

2002 is 20 years ago, which is roughly a generation. Even my generation, which technically remembers this time, doesn’t really remember. We have offloaded so much of our imagination to these devices that we literally can’t imagine a world without them. But there was. Today someone living that lifestyle would look insane, but that’s really a case of the world going mad more than anything else.

30 years ago, my parents had pagers and I was still a child. I could reach them, indirectly, at any time, though the phone in my father’s office was still rotary dial. This was also a generational change. Today the very idea that one could be uncontactable is anathema, but people went to movies and travelled and seemed to survive. I don’t remember any difficulty because we didn’t know what easy was at that time. But now things have become so convenient that it creates its own complications. When you can be reached anywhere, you can never really be anywhere at all. Other locations are pulling on you all the time.

You can, of course, drop out of this lifestyle anytime you want. The way time (or evolution) progresses is not necessarily by destroying the old but layering new things over it. Crocodiles and sharks exist largely in their vestigial niches, and landlines and dumbphones do too. You can still use all these things that were normal just a few generations ago, you just look like a loony. The lifestyle of a normal person from 20 years ago seems positively monk-like today. The lifestyle of someone from 30 years ago seems like a forest-monk. That’s how far our sense of normal has been pushed.

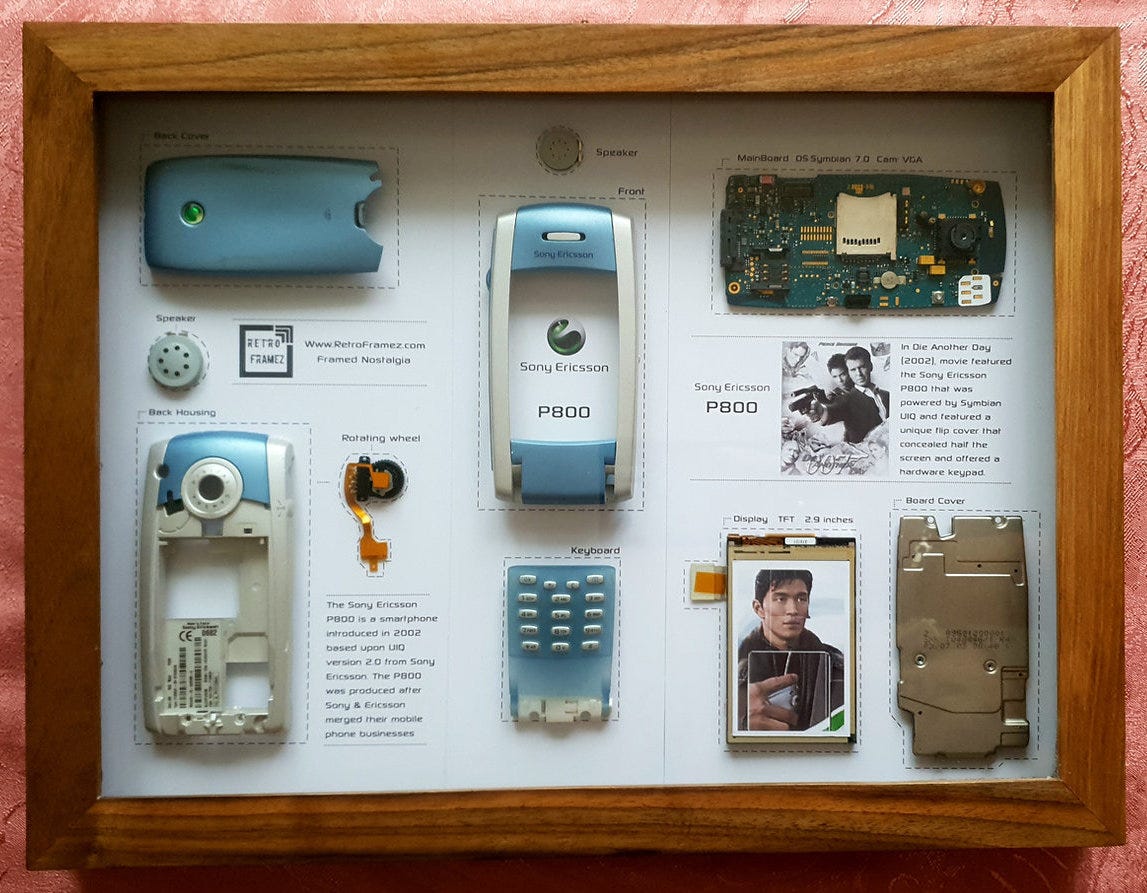

I can still feel it weird because I grew up right on the cusp of that change. I bought a Sony Ericcson P800 in 2002, a proto smartphone with a pop-out stylus and Internet settings that required an hour on the phone to setup. It was slow as shit, the camera was terrible, and it was magical. I could listen to music on the go, take photos of friends at parties, look up restaurants on the road. We take it all for granted now, but this was unbelievably strange at the time. I remember leaning on a Montreal street corner typing something and people looking and talking about it, like “what’s he doing?” Now it’s completely unremarkable. But it’s still remarkable. If you remember.

I still remember being hopelessly lost (no maps). I remember being completely bored. I remember not being able to answer questions, not being able to scratch every itch that troubled my brain folds. I remember not being able to talk to someone because they weren’t home. I remember waiting, and planning ahead, and yet I don’t remember these things being inconvenient at all. It’s more that modern conveniences made them inconvenient. You can’t miss what you don’t have, but once you have it, you can’t live without it. They say knowledge is power, but they don’t say over whom. In many ways our conveniences rule over us. We can scratch any itch, and yet we’re somehow itchy all the time. These facts aren’t unrelated. They’re causal.

Today the only time I go without connectivity is literally if I go on a meditation retreat. There you have to leave your phones behind. It’s a monastic sacrifice today yet this was just how everyone lived not so long ago. Now it’s a deprivation reserved for spiritual retreats or incarceration. Whenever I’m in this state I’m amazed at the sights and sounds I perceive, through the altered state of boredom. And yet I grew up in this state. It’s amazing how we forget where we came from.

A normal person from 20 years ago would look like a monk today. And perhaps in 20 years this scatter-brained state will look idyllic. We’ve spent a long time pursuing the idea that more information, that more connection leads to more understanding, but it doesn’t. Understanding has always been engraved behind our eyelids, slipping in and out of our grasp with every breath. We keep piling on more and more information from every corner of the globe without ever looking at what’s in front of us. We stray further and further from the monastic to the spastic, thinking we’re getting more enlightened and we’re not. The phones light up, but the faces in front of them remain dim. Our city lights blot out the stars, 24/7 news blots out history, and buildings blot out nature. We live in a fallen age, thinking we’re rising. We used to be monks.